Remember, remember, the fifth of November, gunpowder, treason, and plot!

Why blur isn't all bad

Banishing blur from your photos

Organising a photo walk? 10 things to consider

The London Long Exposure Photo Walk

The winners of our Patience is a virtue long exposure competition are...

It took some serious deliberation. There were a lot of emails between us. There was even the odd expletive. Finally, however, Haje, Tom, and I have selected our five favourite photos from the Photocritic Long Exposure Competition. In no particular order I present to you the winners of Patience is a Virtue:

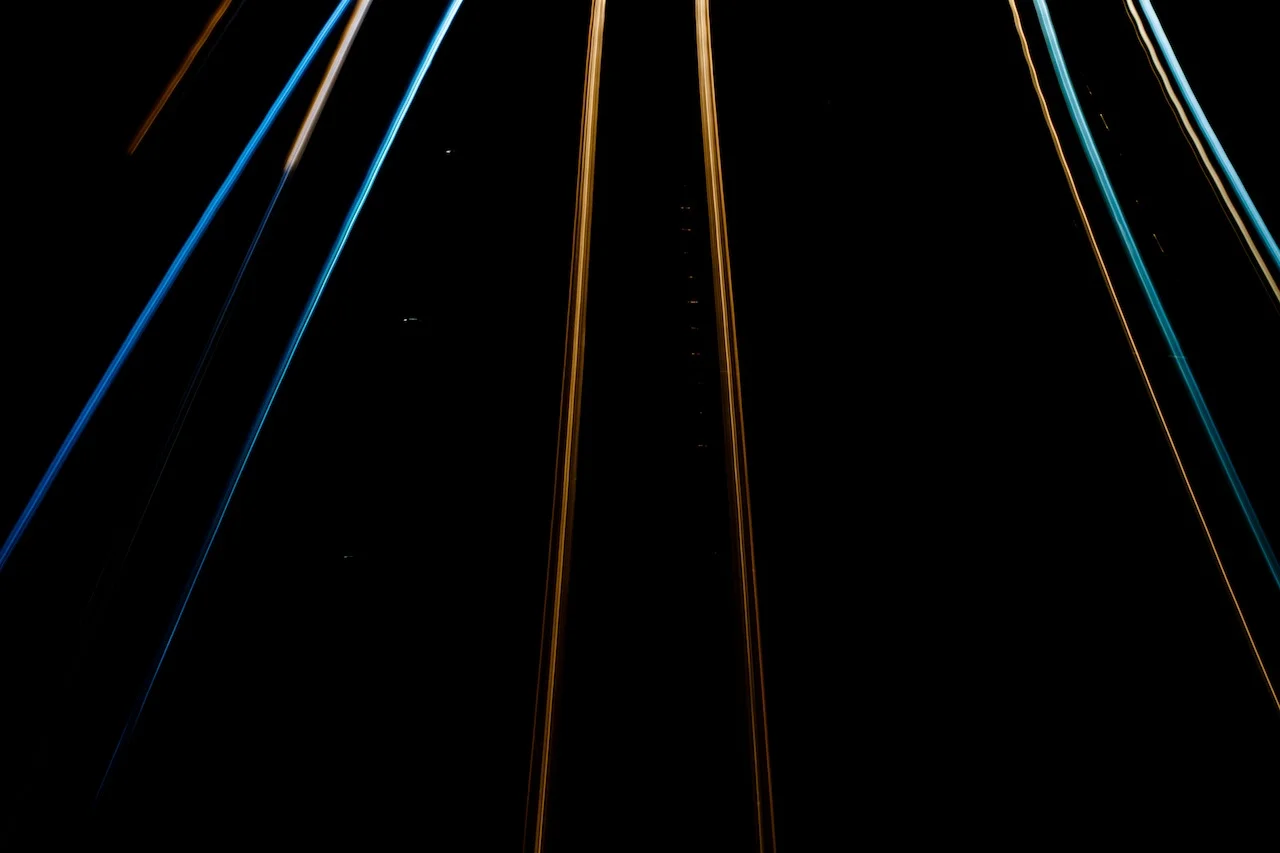

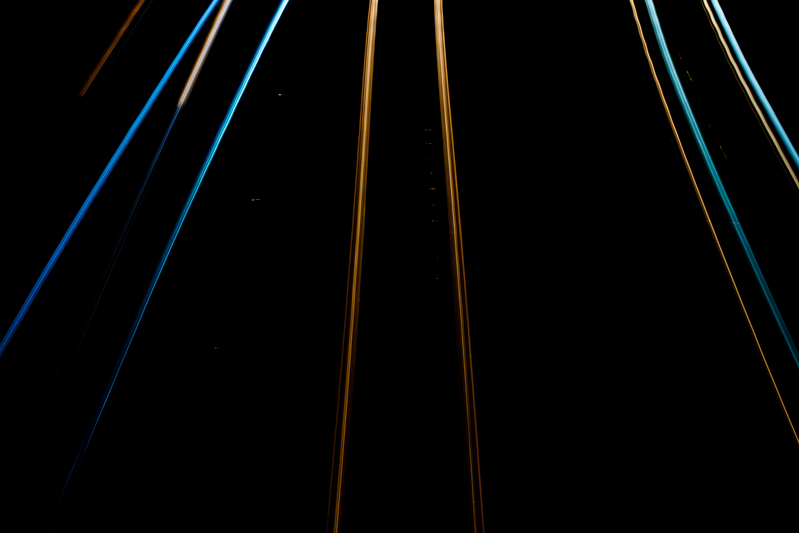

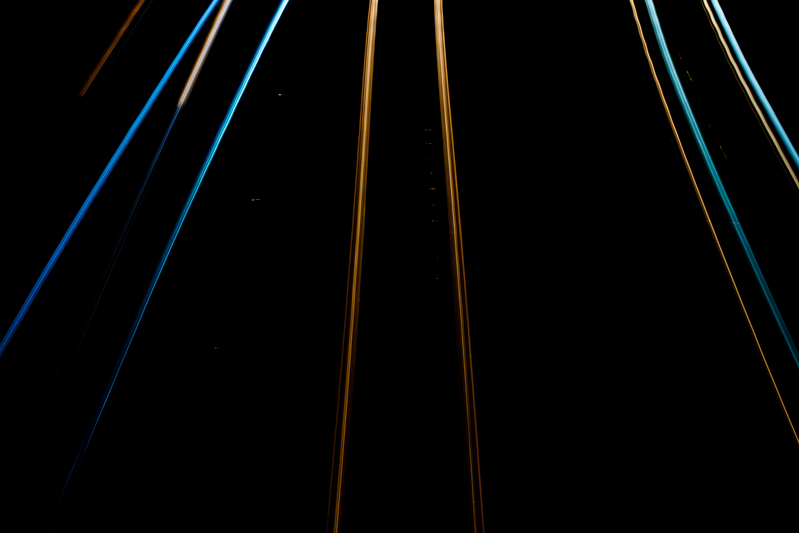

Set Fire to the Rain by Cybjorg

Sunrise at Botany Bay, Edisto Island by Luke Robinson

Tower Bridge traffic by Nick Jackson

Blades of Light by Paul Shears

and Cairngorm Panorama by Ian Appleton

Many congratulations to the five of you! I shall be in contact presently to enable to you claim your Triggertrap gift card prizes!

We'd also like to say thank you to everyone who entered and made our lives a little bit tricky when it came to selecting a winner. As Haje said when we first sat down to draw up a shortlist of our favourites: 'There's some serious talent there!' Please do go look at the selection in the Flickr pool: there are some inspiring images.

Last call for the Photocritic long exposure competition!

British Summer Time ends this weekend&Mdash;at 02:00 on Sunday, to be exact—which means that time is running out for you to submit your long exposure photos to our competition. We won't be accepting any more entries after the clocks move back, so if you want to be in with a chance of winning a £40 gift card for the Triggertrap shop, you'd better get your skates on.

All of the competition's rules and regulations, not that there are many of them, can be found on the Flickr pool page, the same place to which you need to submit your entries. There've been some cracking shots submitted so far, but we'd really love to see more in the pool!

Good luck!

Prepare yourself to capture the meteor shower from Halley's Comet's impromptu fly-by

Halley's Comet made its last swoop past earth in February 1986. I remember it well because I was in primary school at the time, learning about the Norman Conquest. In addition to the boos, hisses, and cheers elicited by the key players and the confusion surrounding Harold Godwinson's death, Halley's Comet plays a starring role in the Bayeux Tapestry, which documents the invasion of a loosely termed 'England' by William of Normandy and his cronies. That we had the opportunity to experience the same celestial phenomenon as the people we were learning about, all of whom lived 900 years before us, was rather special. The timing could not have been better for a memorable series of lessons.

Seeing as Halley's Comet is on a 76 year schedule, it isn't expected again in all its glory until July 2061; however, we are being treated to an impromptu meteor shower in the next few days. The comet is likely to deposit a trail of cosmic dust into our atmosphere on 21 and 22 October 2014, giving us a shooting star display visible to the naked eye.

If that isn't an excuse for trying a little night photography, I don't know what is. So apart from the hoping for clear skies, what else can you do to maximise your chances of capturing the tail lights of Halley's Comet?

The basics

Whatever means you use to take your photos, capturing a meteor shower is fundamentally the same process: shooting a series of long exposures. There are a few options for how you go about it, but once you know that bit, it's fairly simple.

Location

The darker the sky, the better the chance you will have of being able to see the streaks of light as the comet's dust burns through the atmosphere. Ideally, then, you need to be somewhere that doesn't suffer from too much light pollution and has an uninhibited view of the sky. Open and accessible heath- or park-land that's relatively far from city lights is ideal; just be certain you're not venturing somewhere you shouldn't, either because the land is privately owned or you're disturbing a sleeping bull! I'd advise not going alone, either. Shooting in secluded or isolated locations is not necessarily a solitary activity.

Equipment

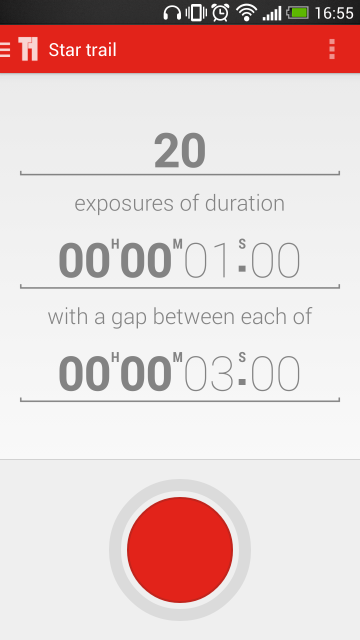

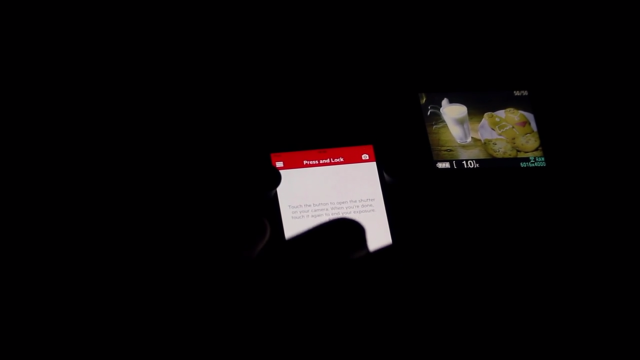

Shooting the night sky means long exposures, so you're going to need a tripod, and an intervalometer will ensure the best results, although you can get by without one. Naturally we recommend Triggertrap, especially because its star trail mode makes life easy, but your mileage may vary. For your lens, a fast, wide-angle lens is advisable. You're never quite certain where they'll start or where they'll end, so the wide-angle provides you with sufficient flexibilty, and it gives you the option to introduce an interesting foreground to the shot, too. The darkness of the sky means that you need fast glass to let in enough light. And an empty memory card is a good idea: you'll be taking a lot of images.

The set up

While shooting stars can turn up anywhere, they are most likely to cluster around a single point called the radiant. Don't aim your camera directly at the radiant, when you've worked out where it is, but about 45° to one side of it. You also want to compose the frame so that it is visually interesting beyond just the shooting stars. Think about including something intriguing in the foreground. Turn off the auto-focus, use as wide an aperture as you dare—you might not want it all the way open for sharpness—and focus to infinity.

The best option to photograph a meteor shower is very similar to capturing a star trail image, when you compile a series of long exposures shot over a significant period of time into a single image, but with a few key differences. You can read our star trail tutorial here, and if you'd like to shoot a star trail image that hopefully captures some shooting stars, go right ahead. Otherwise, you can tweak the process and use it as the basis to capture a series of photos from which you'll select the ones that show shooting stars streaking across them.

What are these tweaks you'll need to make, then? First and most obviously, you'll not compile all of your frames into a single image that charts the movement of the celestial bodies across the heavens. Instead, you'll pluck out the indvidual images displaying shooting stars, or maybe composite several images showing shooting stars.

Second, you might need to use a slightly shorter shutter speed than you would with a star trails sequence, to ensure that you don't capture the turn of the earth. With a star trails shot, the movement of the earth is exactly what you want, but with single meteor images, not so much. Between 10 and 25 seconds is recommended, but a few test shots should help you to decide what you need to use. This slightly shorter shutter speed will require you to adjust the ISO to get a good exposure, too.

Finally, you can chance not taking your series of images with very short intervals between them, as you would with a star trails sequence, but leave the gaps a little longer. That means you might miss a few opportunities, but the law of averages suggests that if you shoot over a period of a few hours, the odd photo will have a shooting star zooming across it.

When you have set the focus and established your shutter speed and ISO, you will need to set your intervalometer as you would for a recording a time-lapse sequence, using the exposure time that worked best in your test shots. If you're using Triggertrap's star trail mode, set the exposure time that you established in testing with your chosen interval between frames, and select the number of frames you want to take. With a slightly longer interval between frames, say five or ten seconds, you could shoot for hours!

If you don't have an intervalometer, there's no reason why you can't try your hand at meteor shower photography. Instead of relying on a remote triggering device to release your camera's shutter, you'll be doing it yourself, which might get tiresome. Just as you would with a star trail-based sequence, aim your camera in the right spot and focus to infinity. With your camera in manual mode, use the widest aperture you can, select a shutter speed between 10 and 25 seconds, adjust the ISO accordingly, and press that trigger. Over, and over, and over, again!

Remember to keep warm, and here's hoping for clear skies.

Patience is a virtue, but we're impatient to see your long exposure photos!

You've just under a week left to submit a maximum of five of your favourite long exposure photos to our competition, and be in with the chance of winning one of five £40 gift cards for the Triggertrap shop. We've already had some terrific entries over in our Flickr pool, but we'd love it if you made the judging even more difficult for us!

To enter, upload your image to Flickr and share it in our competition pool. There are some rules and regulations, you can find them on Flickr pool page or here on Photocritic.

We can't wait to see your photos!

Patience is a virtue - a long exposure photo competition

Good things come to those who wait, or at least good things come to those with the requisite degree of patience required to capture a scintillating long exposure shot. Not only do you land yourself with a fabulous photo, but for this competition, rewards also come in the form of five gift cards valued at £40 to spend in the Triggertrap shop! We're on the look-out for the five best long exposure shots produced by you lovely lot. That's not the royal or editorial 'we', by the way, but Haje, Tom, who's Triggertrap's Head of Photography, and me. We don't mind what kind of long exposure shot you try: from urban scenes to light painting to smoothed waterfalls. What we want to see is a longer-than-expected shutter speed being used to creative effect to tell a story. We want to see images that leave us giddy with admiration.

Flickr is providing the image-hosting power for the competition; all you need to do is share your photos—up to five per entrant—in the Patience is a virtue Flickr pool before British Summer Time ends. So that's 01:59 (BST) on 26 October 2014. Consider it preparation for longer nights if you're in the northern hemisphere. We'll do the rest, and hope to have the results by Guy Fawkes Night. (Or 5 November 2014.)

(Un)Usual rules apply: you need to own the copyright to the images you submit; you shouldn't have done anything icky to achieve them (like sell your granny); you keep the copyright but we (that being Photocritic and Triggertrap) will want to be able to display it in conjunction with the competition; the prizes are non-transferable and can't be redeemed for cash; you can't be associated with Photocritic or Triggertrap to enter; the judges' decision is final; entry is at your own risk (quite what might happen to you because you enter I'm not sure, it's not like we're cannibals threatening to eat you, but we can't be held responsible all the same); photos have to be submitted to the Flickr pool before the closing date of 01:59 (BST) on 26 October 2014; and it's our competition so if we need to change the way it operates or the rules or heaven forfend chuck you out, we can.

That's about that. But if you need any advice on long exposures, you might want to check out our articles on shutter speed, bulb mode, zoom bursting, and light painting. Good luck: we can't wait to see what you produce!

And the results are in! You can see them here.

Riding the waves to smooth water images

Photos that feature milky-smooth flowing water seem to have a Marmite effect on people: they're either loved or hated. I'm often rather ambivalent towards them, but it doesn't mean that it isn't a useful technique to have up your sleeve if you're faced with a weir or waterfall and you want to capture an image with smooth-looking water that has a sense of flow to it.

There's no great secret to shooting a photo that has water flowing through it that looks smooth: it's done using a long exposure. The slow shutter speed captures the the water as it moves, making it blurred. The blur, in this instance, gives the water a smooth appearance.

Shooting long exposures in daylight hours comes with an inherent problem, however. Over-exposure. Our cameras' sensors are capable of detecting far more light than we think they are, and even using the lowest possible ISO and smallest available aperture, a long exposure can result in an over-exposed photo when taking during the day. To get around this irritation, you might want to try a neutral density (ND) filter over your lens.

ND filters are grey filters that cut down the amount of light that enters your lens without affecting the colour of your images. They come in different grades, or densities, blocking out between one stop and 12 stops of light. Screw one over your lens and you'll give yourself a great deal more flexibility when it comes to shooting daytime long exposures.

Then of course you'll need a tripod. You might want to capture the motion blur of the water, but you'll want to avoid camera-shake and the rest of the scene getting the wobbles. Even though you'll be using a very small aperture with an enormous depth-of-field, still think carefully about your framing of the shot and its point-of-focus. Make sure it's telling a story.

Obviously you'll need to have your camera in manual mode to ensure that you can adjust the shutter speed, ISO, and aperture to get the photo that you want. Almost certainly you will need to use the lowest ISO and smallest aperture avalable. When it comes to shutter speed, you might find that you need to venture into bulb mode to get the shutter speed you need. And we recommend that you use a remote shutter release to prevent jolting your camera on its tripod and shifting its focus, too.

Then it's a case of hitting the cable release and leaving the camera to do its thing.

All images are courtesy of Triggertrap. You can learn more about using remote releases on the awesome Triggertrap How-to site!

Painting with light - a how-to to get you started

If you'd like to try a more unusual approach to lighting a photo, whether that's because you want to experiment or because you don't have access to studio lights, you might want to consider light painting. This isn't the type of light painting when you make patterns and shapes and designs with light sources to create your image, but using light sources to illuminate your scene during a long exposure. At its simplest, it involves outing the lights, setting your camera to bulb mode, and using a torch to 'paint' light onto your subject. Want to give it a go? Read on!

Kit

You don't need anything especially fancy for light painting: a camera on a tripod, a scene that you want to illuminate, and a torch are the minimum requirements. You might find it easier to control your camera's shutter using a cable release for flexibility and when you're more confident you might want to try some more advanced techniques, but let's start here.

Imagining your scene

Before embarking on your light painting adventure, it's best to think about the scene that you want to illuminate and the story that you want to tell. While you might herald some impressive results from waving your torch about in random formations, that's unlkely to result in the image that you anticipated. Take a little time to consider your subject and how you want to light it.

Camera!

Scene set and lighting scenarios imagined, you need to secure your camera on your tripod and select your exposure. For light painting, try bulb mode controlled by a cable release, a low ISO, and an aperture that gives you the look you want. You'll need to manually focus on your subject, too!

Lights!

Turn out the lights and start your long exposure.

Action!

Use your torch to begin to paint light over your subject. There's going to be some trial and error involved in getting the effect that you want, but that's half of the fun! Not keen on what you see? Try it again!

Stretching your creativity

When you've mastered the basics, you can push your experimentations further. Try introducing coloured light to your images by covering your torch with coloured gels, or even sweetie wrappers. You can make cut-out filters to shape your light. Or direct your light more accurately with a snoot manufactured from cardboard and gaffer tape. You're not limited to inside, either. Try light painting buildings and monuments or flower pots - whatever takes your fancy and you've sufficient fire-power to illuminate!

This is something that doesn't have to cost the earth but can render some fabulous results.

Much of this, including all the images, is based on the fantastic How to paint a still life with light tutorial found on Triggertrap's How-To microsite, and it's reproduced with permission. Triggertrap How-To is full of great content for making the most of your camera. You should take a look.

Today's World Photo Day! What are you going to do to mark it?

Today is World Photo Day. If you're wondering how a 2009-invented celebration of the visual medium came to be on 19 August, it's because that's the day in 1839 when the French government announced that it had purchased the patent to the daguerreotype method and made it a gift 'free to the world'. Armed with that snippet of information, the pressing question is, what are you going to do to mark it? For anyone in need of a little inspiration, here are some Photocritic suggestions to mark World Photo Day.

1. Try something new

Photography is a learning curve. There's always something new to try or with which to experiment, so pick something you've not done before and give it a go.

May we recommend, in no particular order and certainly far from exhaustive:

- High-speed photography

- Street photography

- Macro photography

- Infrared photography

- Nude photography (that's photographing nude models, rather than taking photos in the altogether; but if that floats your boat... why not?)

- Long exposure photography

- HDR photography

- Panoramic photography

- Flash photography

- Astrophotography

2. Go back to basics

The technological wonders that we can perform with our cameras today can sometimes obfuscate the simplicity of photography. It's painting with light. So why not go back to basics: pick up a pinhole camera and rediscover the perfection of capturing light in a box.

3. Have a print made

How many of your photos are hanging on your walls and how many are stuffed away on hard drives as binary files that never see the light of day? Do justice to your skills: pick your favourite image and have it printed to hang on your wall.

4. Set yourself a challenge

We can't all be good at everything. But we can try to improve. Which aspect of photography do you find challenging? What would you like to do better, but find a struggle? Maybe your landscapes come across as flat and dull? Perhaps your portraits fail to capture your subject's spirit? Is your food photography not exactly good enough to eat?

Decide on a point of focus and challenge yourself to improve over the course of the coming year. Read. Practise. Try. Maybe fail. Definitely try again. Keep a record of your experimentations. Come World Photo Day 2015, you can measure your progress.

5. Teach a child to take a photo

There's no better way to share your passion for something than to teach it to someone else. So why not help to develop the next generation of photographers by teaching them how to take photos. It doesn't have to be complicated or difficult, just the basics. We've even got a tutorial to help you.

Dare to stray into bulb mode

When setting your shutter speed, have you ever wound the adjustment wheel so far into long exposure that you've gone past seconds and found 'B' or 'Bulb' on your screen? Or maybe you've noticed that you have a 'B' option on your mode wheel, somewhere between Manual and Custom settings? This is bulb mode, and it allows you to control the duration of the exposure for precisely as long as you would like. It's perfect for exposures in excess of the 30 seconds that most cameras have as their longest shutter speed, or for when you need to be in control, for example if you're practising high-speed photography. First, a quick word on why it's known as 'bulb' mode. Haje has a much more thorough explanation here, but it doesn't have anything to do with light bulbs. It's from back in the day when you could control your shutter speed using an air bulb connected to your camera.

When your camera is in bulb mode, you open the shutter by depressing the shutter release button; as soon as you raise your finger off of the button, the shutter will close. Seeing as it isn't terribly convenient to stand with your finger on your shutter release button for minutes or even hours on end—and it's not fabulous for camera-shake, either—most people use bulb mode in conjunction with a remote shutter release. And a tripod, but that's probably quite obvious.

Plenty of remote shutter releases come with a locking mechanism, so that you don't need to hold your finger down there, either. However, if you go for something such as our much-beloved Triggertrap, you can select from a variety of different modes to control your super-long exposure, including a timed release that lets you set the duration of your exposure down to fractions of a second, a star-trails setting, and even a bulb-ramping option to fine-tune exposure during very long time-lapse recordings.

Even if you're shooting at night, your camera's sensor will be able to detect far more light than you think it can, especially with a very long exposure. Consequently, using a small aperture is recommended. If you're photographing during the day, you might benefit from a neutral density filter to prevent unavoidably over-exposing your images, too.

It is worth bearing in mind that using bulb mode can drain your battery enormously. Don't set off to capture star trails with a less-than-fully-charged battery. Take a spare if you have one, too. It's a complete waste to maroon yourself in the middle of nowhere with limited light pollution only for your camera to keel over halfway into the exposure.

Now that you know what bulb is, what can you do with it? Perhaps you'd like to try some long exposures of landscapes? Or maybe capture some smooth, milky-looking water tumbling from a fall. You might want to try your hand at a star trail, or have a go at light painting. You could even grab a flash adapter and have a crack at some high-speed photography and burst some water balloons. So many options presented to you with so much time from bulb mode!

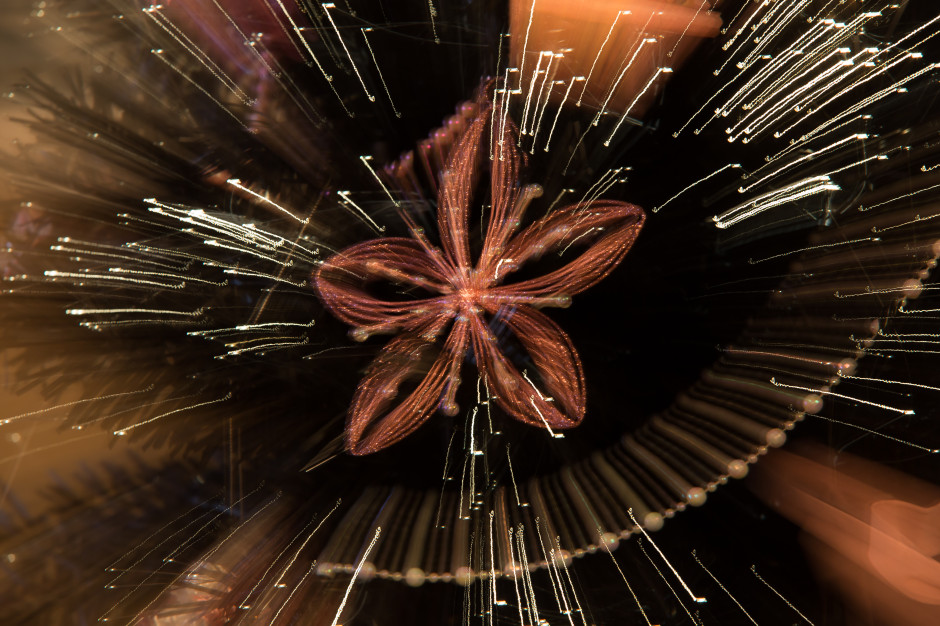

Christmas is coming: zoom bursting!

The twinkling lights and glittering decorations of our Christmas tree are always far too good a photographic opportunity to pass up. Last year they were my testing ground for a Pentax X-5 that I had to review. This year, I decided to play around with zoom bursting, to make it appear as if the lights are bursting out of the image. While the abstract motion effect of a zoom burst might look as if it's a pain to achieve, it actually isn't that hard. You definitely need a zoom lens on your camera and preferably a tripod; then you just need a bit of patience to get it right.

Compose your frame and focus on your subject. It's actually one occasion when centre-focusing really does work and doesn't leave your composition feeling flat and dull. But of course, it's whatever works for your photo. You'll probably find it easiest to zoom in as close as you can and then lock your focus or set it manually.

In order to achieve the motion effect you'll need a slow shutter speed, so that you have sufficient time to turn the zoom ring on your lens. If you're not confident using full manual control, do flick your camera into Shutter Priority (S or Tv) mode. For this series of photos I experimented with exposure times ranging from one-and-half seconds to ten seconds. The optimal speed seemed to be five seconds, but of course it is going to to vary depending on your subject.

I kept the aperture fairly small and the ISO relatively low. Being a long exposure shot, there was a strong possibility that it would come out over-exposed if I adhered precisely to the camera's meter, so I under-exposed by a stop-and-half. If I'd been shooting in Shutter Priority mode, I would have achieved the same effect by applying exposure compensation.

When you're ready, depress your shutter button, or use a remote release to help avoid camera shake, and then steadily zoom out throughout the course of the exposure. If you'd like to ensure a little more definition for your subject, don't begin to move the zoom ring immediately, but let it rest for about a quarter of the exposure time and then start to move it.

In most cases, you will probably want to zoom out to give the impression of the subject bursting forth from the image. I also played around with zooming in and rather liked the effect. It's all going to depend on what works for your photo.

Once you have the basics down, it'll be a case of playing around to see what looks best. Have fun!