When you tell people that image processing and manipulation isn't anything new, but is just about as old as the art of photography itself, you can get some funny looks. Many of the processes that we carry out without a second thought were equally normal for analogue developers. Depending on how proficient you are with Photoshop, compositing might be faster today, but it's not new. Think of Man Ray and his image Le Violon d'Ingres. And beautifying subjects with the help of a brush was a far from alien practice for Cecil Beaton. Yes, really.

The difference is that now the ubiquity of editing suites means that techniques that were once the preserve of skilled darkroom practitioners are accessible to anyone with a computer. The degree of skill required to complete subtle, effective, and credible edits is still high, but the mystery has gone. Or rather, the mystery has assumed a new narrative as the dark arts of the darkroom remain under wraps.

To try to set some of that record straight, here's an extensive, but not necessarily exhaustive, list of the techniques that bridge the analogue and digital divide.

Crop

Have you noticed how the crop icon is a variation on a theme, in almost every editing package you encounter? That's because it's based on the tool that would be used to crop and resize images in the darkroom.

[gallery ids="6782,6783,6784"]

Brushes

The brush icon is another familiar one, whether you're in Photoshop or Pixelmator or Aperture or GIMP. Brushes were used extensively in the darkroom, to define edges or enhance details, to hand colour, to spot correct, to complete just about any task for which you might now use a digital brush.

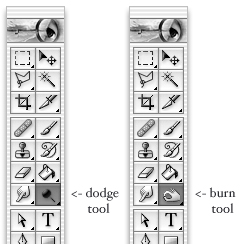

Dodging and burning

Haje has already written an article that explains why the dodge icon resembles a lollipop and the burn one a fist. Of course, they're techniques that were used in the darkroom to lighten or darken specific areas of an image as required. The dodging 'lollipop'—or piece of black paper on a stick—could protect the photographic paper from too much light during the development process, thereby keeping the areas in question lighter in the final image. The fist would be your hand, controlling how much light got through to darken areas of your photos.

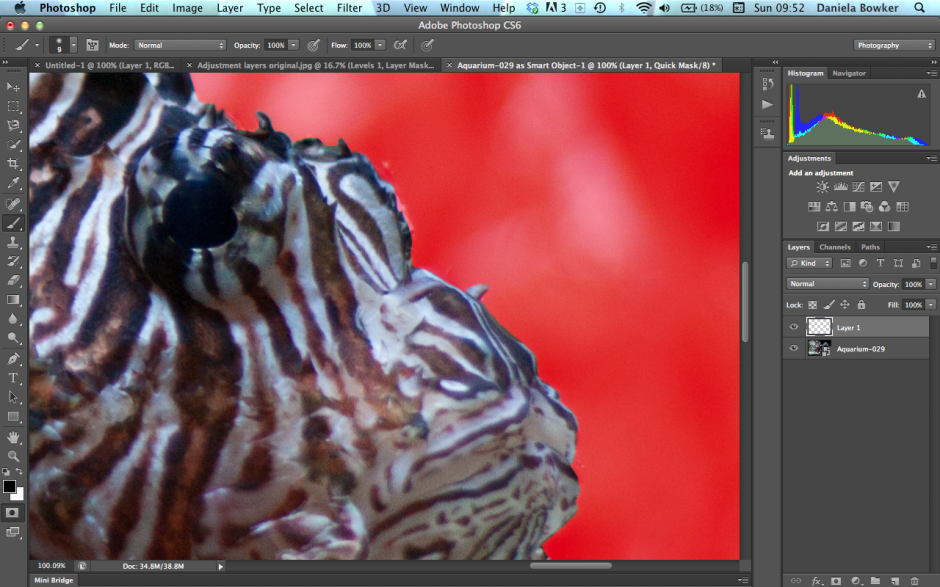

Masking

Using red to distinguish masked from unmasked elements in an image wasn't an arbitrary choice by software engineers. That too is a hangover from darkroom days. Mask an area that you don't want developed with red, gel-like rubylith and the light won't be able to penetrate it in the darkroom, so it won't be exposed. If you've ever found yourself irritated when masking a complicated outline in Photoshop, imagine what it would be like doing it with a scalpel!

Sharpening

Yes, there's a reason why the sharpening tool in Photoshop is called the Unsharp Mask. Again, Haje has a comprehensive explanation here, but the short answer is that images were sharpened using a not-quite-sharp positive of the image to make a mask (an unsharp mask) combined with the negative. The blurriness of the positive image should work with the negative to create a sharper final image.

Split-toning

Maybe you use the split-toning feature in Lightroom to create cross-processed effects, or to give a golden-hour glow to your photos, or perhaps to correct the white balance in your images. But it was originally a darkroom technique that allowed different tones to be present in the highlights and shadows of an image. Split-toning was something of a dark art, relying on the interplay of different papers and different chemical toners deployed after the standard developing and fixing process to produce different colours in the final image. Getting the balance right with your sliders might be a frustrasting experience now, but I'm sure it beats fiddling with gold-, selenium-, and sodium-based chemicals!

Contrast

It might be simple to adjust the contrast in your photos on a slider in a digital darkroom, but you had at least three ways of doing so in an analogue darkroom: with graded papers, with variable contrast paper, or with filters.

Colour

Unless you're shooting with a Leica Monochrom, you can choose between colour or black and white for any given photo now, switching back and forth between them as many times as you like in a non-destructive editing package. But in the early days of film it was black and white, maybe sepia, or perhaps the vagueries of split-toning, unless you opted to hand-colour your images. Love or hate selective colouring, for some people that was all that they could afford when hand colouring was a time-consuming art form. It isn't just a Photoshop abomination.

Airbrush

Finally, the much-maligned airbrush. It's not just a new-fangled phenomenon that magically reduces the size of an already-stick-thin model's thighs. The airbrush has been removing undesirables from images since at least Stalin's time and Cecil Beaton was famous for slimming his subjects.

I think you'll find, then, that there is very little that's new between the red light of the darkroom and the digital glow of Photoshop.