Did you go to see Wes Anderson's glorious fondant fancy of film The Grand Budapest Hotel? Did you notice how the size of the picture varied depended on the era being portrayed in the story? As the story moved between 1985, 1968, and 1932, the aspect ratio, or size of the image, jumped from 1.85:1 to 2.35:1 to 'Academy Ratio'. This was part of Anderson's story-telling technique: the aspect ratio provided viewers with a visual cue for each period of the narrative. It's also a reflection of the changes to aspect ratio that film and television have experienced over the years. But what about photographers? Where does aspect ratio come into stills?

Frame size

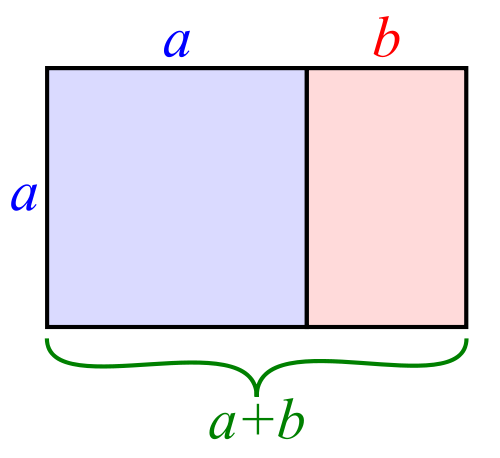

Maybe we need to back-track and establish precisely what we mean by 'aspect ratio' first. It's the size of the image expressed as a ratio, width to height. You'll often see film-making aspect ratios expressed as a value to 1 (like to 2.35:1 and 1.85:1 mentioned earlier), whereas the most common photography aspect ratios are 3:2, 4:3, and 1:1, although there are plenty more besides. If your image has an aspect ratio of 3:2, it will be three units wide and two high. When you come to print it, you might choose a 6×4" or a 12×8" print.

Originally, these aspect ratios were as a result of our film sizes. Lots of medium format cameras produced square, or 1:1, images; 35mm cameras used film that measured 36 by 24 millimetres, giving an aspect ratio of 3:2. What's referred to in the film-making world as 'Academy Ratio' is very close to 4:3. It's also the common aspect ratio you'll find in smartphone cameras as well as Micro Four Thirds and some medium format cameras. 16:9 is usual for recording video.

While our digital sensors might preserve these aspect ratios in their physical dimensions, at the press of a button I can switch between 3:2, 4:3, 16:9, and 1:1 on my camera. And when I import an image into Lightroom or edit it in Snapseed, I can select from 1:1, 3:2, 4:3, 5:4, 7:5, 8.5:11, 16:9, or settle upon an entirely idiosyncratic free-styled aspect ratio. But why would I want to?

Composing the frame

It's about composition, and dividing and filling your frame.

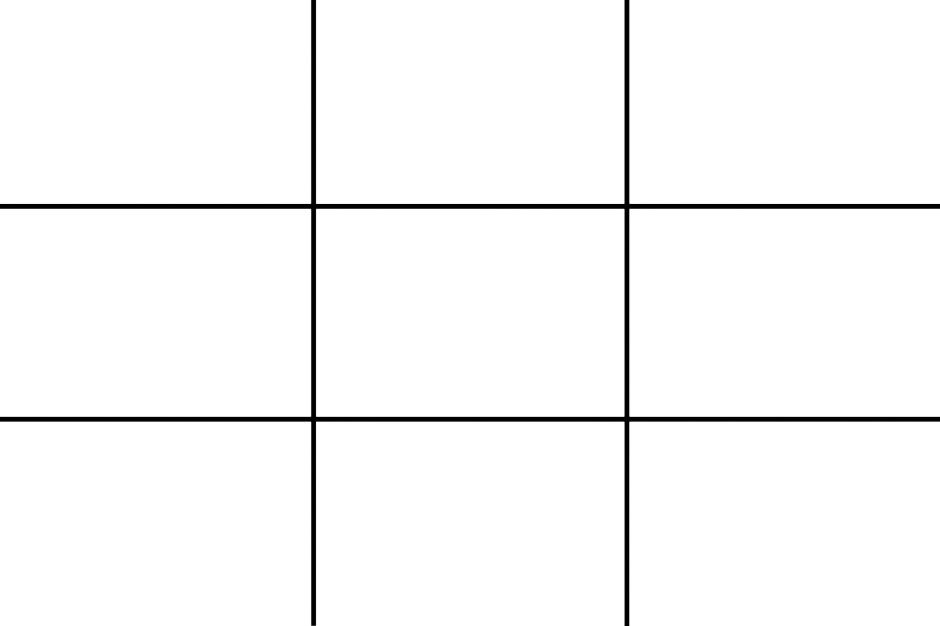

Photographers talk a lot about subject placement, about the different rules that can be used to divide the frame, and about negative space. All of these elements contribute to creating visually appealing, dynamic images that draw the eye. It follows, then, that the dimensions of the frame will have an impact on composition: on where you place your subject and how much space surrounds it and how you divide your frame.

Different rectangles

We've already written about the square crop here on Photocritic, and how the eye has a tendency to move around a square frame, as opposed to across it, which it does with a rectangular crop. When changing between 3:2 and 4:3 crops, are there any considerations that need to be made?

At its simplest, you have more space to fill with a 3:2 frame. Depending on your style and your subject, this can mean your subject has more room to breathe compared to a 4:3 crop. But it can also mean your subject has that bit too much space and feels a touch lost. You certainly need to be aware of this when you're shooting; and indeed if you intend to have prints made.

When I photographed my cousin on his graduation day, I adhered to my preferred 3:2 aspect ratio. It was how I approached filling the frame on the day and, consequently, how I processed the images afterwards. However, when my aunt had her prints made, she opted for a 24×18 canvas. I had to re-crop her favourite shot in a hurry. You can see both of them here. Can you see why I prefer the 3:2 aspect ratio in this instance? It doesn't feel nearly as squashed as the 4:3 version does.

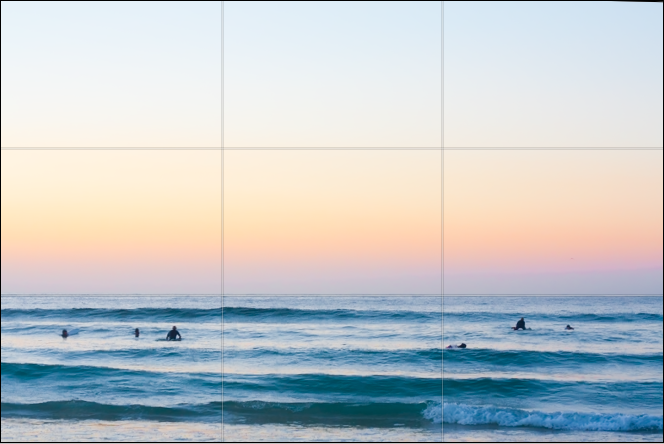

If you compare these sunset photos, you can see how much of the view the 4:3 version loses when compared with the 3:2 aspect ratio. It can prove difficult to fill the extra space in a landscape shot, but sometimes you need it, too.

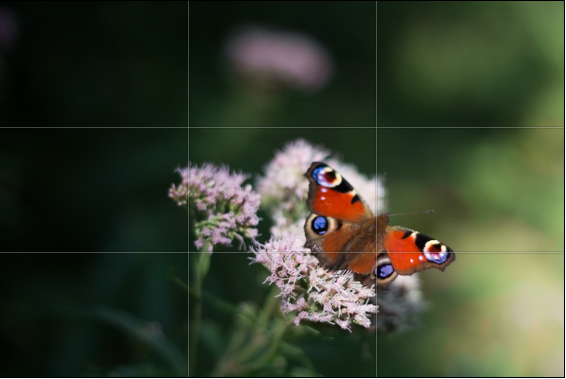

Of course, you don't have to adhere to 3:2 or 4:3 aspect ratios. I decided that 4:5 worked best for this bee enjoying the Sicilian springtime flowers. The more compact frame focused attention on the bee better than the larger 2:3 version.

Don't forget, if you switch from landscape to portrait orientation, then the aspect ratio will alter format accordingly. Width always goes first, thus 3:2 will change to 2:3 and 4:3 becomes 3:4. Or in the case of the bee, it's 4:5.

Opting for a different aspect ratio doesn't necessarily mean that you need to use a different compositional rule; however, in some circumstances, you might find the Golden Ratio preferable to the rule of thirds. It depends on your vision for the image. But do think about how much space you need around your subject. If you're struggling to fill it, think of trying 4:3; if it looks squashed, consider 3:2. Or try something else. Try not to feel too constrained by the constraints of aspect ratio.

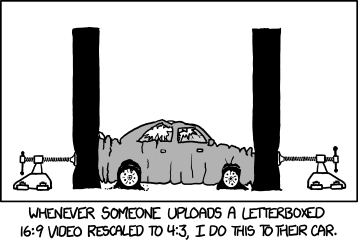

But I will leave you with closing thoughts from xkcd. Who could put it better?