For literary types, a vignette can be either an anecdote or short story, or a illustration—often foliage-inspired—found on chapter headers. For photography types, a vignette is the gradual fall-off of light from the centre towards the edges of the frame of an image. If you enjoy Instagram or play around with Snapseed, you might know a vignette as a cool effect that you can add at will. They are, however, far more than just an effect. Thus we present to you the self-contained, but not necessarily short, Photocritic guide to vignettes, without any vines.

Types of vignette

Photographic vignettes occur because of natural, optical, mechanical, and technical reasons and can appear whether you prefer analogue or digital technology. While we might associate vignetting with vintage, it's hardly stuck in the past. Digital sensors managed to introduce their own form of vignetting, and a great deal of it is down to lenses. What are we looking at, then?

Natural vignetting

You are most likely to see natural vignetting when you use a wide-angle lens. It's a gradual darkening of the image that happens because light reaches the sensor (or film) at different angles. As the photons need to travel further to reach the edges of the sensor, they lose their strength, hence the darkening.

Optical vignetting

Lens design is primarily responsible for optical vignetting; the lens' barrel prevents light reaching the sensor evenly, and the lens elements stacked up on top of each other can have an impact, too. Optical vignetting is more pronounced when shooting at wider apertures; stop-down a bit and you can reduce its prevalence.

Mechanical vignetting

If anything physical blocks the passage of light to the sensor, for example a lens hood or a filter, it can cause a vignette. This is the easiest vignette to correct: check all of your accessories are properly attached.

Pixel vignetting

The pixels towards the edges of a sensor aren't always able to record light at the same intensity as those closer to its centre, mostly because of the angle at which the light hits them. This can lead to a darkening of the image towards its edges. Sensor manufacturers have caught onto this phenomenon, however, and have introduced compensations to rectify it.

Why add a vignette?

If a vignette is regarded as an aberration, why would you want to add one deliberately to an image? When used reservedly, they can bring focus to your subject and draw your eye into the frame, particularly in portraits. First because they allow for fewer distractions at the edges of the frame, but also because they mimic the natural effect of the eye. We don't see sharply all the way to the edges of our vision, and a vignette's fall-off has a similar impact on our photos. They reproduce a degree of 'normality' that we can find pleasing. The essential factor in applying them is to be subtle, therefore.

Adding a vignette

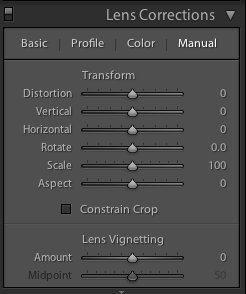

Lightroom allows you both to add artificial vignettes and to correct those produced as the result of optical or mechanical aberrations. If you need to correct a vignette, reveal the Lens Corrections panel, where you can also adjust various types of lens distortion, and nudge the Lens Vignetting sliders until your photo looks 'right'. (They sit beneath the Manual tab.) Easy!

This is also an easy means of adding a subtle vignette to a largely uncropped photo, too. It doesn't let you over-do it, which is the cardinal sin of adding vignettes, and there aren't too many factors to consider. It's sneaky, but if you're working with a cropped photo, not helpful. For a cropped photo, you need to head to the Post-Crop Vignetting options in the Effects panel.

Here, you have far more control over the vignette that you add to your image.

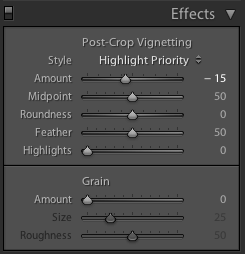

With three drop-down options and five sliders, it might appear as if adding a vignette is more trouble than it's worth, but it's relatively straightforward. We'll deal with those drop-down options first.

Highlight Priority, Colour Priority, or Paint Overlay?

Highlight Priority, Colour Priority, or Paint Overlay? Highlight Priority allows for highlight corrections and recovery, so is good with images that have specular highlights, but it might have an adverse impact on the colours in the darker areas of your image. If you're working in black and white, colour shifts won't be an issue, so it's an easy choice.

Colour Priority won't produce such a pronounced shift the colours in the darker areas, but it won't let you recover highlights, either. Julieanne Kost, who works for Adobe, reckons it's a more subtle effect. You might want to consider this if your photo is in colour.

As for Paint Overlay, it is supposed to mimic the effects of overlaying your photo with either black or white paint.

To walk through the sliders, I'm using a photo of my nephew Wil for demonstration purposes. It's been cropped, converted to black and white, and had all of its other adjustments made. The last thing on the list is the vignette. That's how you should apply one, too.

Amount

The Amount slider is the crucial slider when adding a vignette. It determines how strong the darkening or lightening of the edges of the frame will be. Set it at -100 and you'll have deep black edges; conversely, +100 will leave you with bright white edges. Without adjusting this slider, none of the other Post-Crop Vignetting sliders will have any impact on your image.

From now on, we'll look at all the other sliders having an effect with the Amount set to -100. It offers the clearest demonstration of their impact.

Mid-point

The Mid-point slider controls the size of the vignette from the centre of the frame. It naturally sits at 50 points; reduce it to 0 and you'll produce a vignette that encroaches far into the frame.

Set it at 100 points and it'll sit closer to the edges of the frame.

Roundness

The Roundness slider controls the shape of the vignette. At 50 points, it's elliptical in shape. Push it to 100 points and you'll have a circular vignette. At 0, it's a rectangle with rounded corners. (By pushing all of the Post-crop Vignetting sliders completely to the left, you'll create a rounded-corner rectangular frame effect for your photo.)

Feather

To control the strength of the transition between the vignette and the centre of the image, adjust the Feather slider. 100 points ensures a very subtle transition; 0 points is a sharp transition with a hard edge. Its native position is 50 points; I don't often vary far from there.

Highlights

Finally, we're left with the Highlights slider that starts at 0. Why might you want to increase the highlights slider? It prevents the vignette being applied too heavily to highlights in the image and helps to keep them bright. There's no hard-and-fast rule for this slider; it needs to be adjusted on the merits of each image.

It's important to note that the Post-crop Vignetting panel applies the vignette centred according to the crop. If you want to introduce a vignette that works around an off-centred subject, you'll need to do that using Radial Blur. That's a whole different article, however.

Other vignette options

If you don't use Lightroom, you can add a vignette using plenty of other editing suites. Photoshop, of course. And Pixelmator. Or Pixlr. Under the 'Centre Focus' tab if you're in Google+. In Apple's Aperture.

The end product

This is my final version of Wil, with a vignette Amount of -15 and a Mid-point of 75. That was it. Remember: subtle is better!