Shutter speeds? Yaaawn. ISO speeds? Oh-god-not-again. Megapixels? Oh puh-bloody-lease, that’s so 2003. The newest frontier of digital photography is dynamic range – and it’s arguably the most exciting (r)evolution that’s happened in dSLR-world so far.

Interestingly, most manufacturers are continually improving the dynamic range of their cameras, but somehow seem to forget to tell us about it – which means that we’re witnessing – or should I say not witnessing – a quiet revolution.

It seems as if ‘dynamic range’ gets forgotten in PR world, where a bigger screen, better battery life or Live View is an easier way of getting regular consumers exited. The real technological leaps have been happening under the bonnet, though, and the result of the ongoing improvements will mean that your next camera will be significantly better than your current one – but you wouldn’t be able to tell from just reading its specification sheet.

So, why, exactly does this make a difference to us as photographers? All will be revealed…

Is this the same as HDR?

Well, we’re still talking about ‘Dynamic Range’, and higher-dynamic-range-than-before at that, but when people are usually talking about ‘HDR’, they mean multi-shot HDR photography, which we covered thoroughly a few weeks back.

Multi-shot HDR is very exciting stuff, and it’s a taste of what is to come, but this time around, we’re talking about single-shot HDR photography and how cameras have been steadily improving over the years.

The improvements have happened so slowly, it seems, that nobody has really noticed – but grab a 5 year old dSLR and compare it to a current-day snapper, and the biggest difference in picture comes from the dynamic range.

Whatevz, can we start from the the beginning, please? What is dynamic range?

The human senses have an absolutely incredible dynamic range – think about it: when you’re inside a concert venue at a rock gig, you can hear every note and enjoy every instrument.

The human senses have an absolutely incredible dynamic range – think about it: when you’re inside a concert venue at a rock gig, you can hear every note and enjoy every instrument.

When you’re in a quiet room, you can hear water flowing through your radiator heater, and the extremely faint buzzing of the phone charger is loud enough to notice. More incredibly still, you can keep a conversation going with someone in the next seat while the jet you are sitting in is taking off, which is a testament to the width of dynamic range which is possible – although that particular example has more to do with psycho-acoustics than your ears themselves.

If you thought your hearing was amazing, well, your eyes are even more incredible. On a bright day, you can see perfectly, but you can also see things by moon- and starlight on a clear night. Not impressed? Try taking a photograph or do some filming by starlight without using a tripod…

Now, these examples of your eyes’ dynamic range come with a caveat – you cannot stand in a dark room and look out into a sunny landscape and see both perfectly – you’ll either be able to see the indoors, or the outside, with the other being over- or under- exposed, respectively. For photography purposes, the important thing is how much dynamic range you can see simultaneously.

Allow me to illustrate: Take a landscape photo where the clouds are nearly over-exposed. The dynamic range of the particular imaging-chip you’ve got, decides how much details you get in the darker parties of the image. The higher dynamic range, the more shadow-details you can expect.

A theoretical camera with perfect dynamic range wouldn’t need shutter speeds – you would select an aperture to get your depth of field, and you could select any shutter speed you need. The sun would have texture, and the deepest, darkest shadow parties of your image would still have detail in them, too. Of course, perfect dynamic range is impossible (for now…) but that doesn’t mean that increasing dynamic range isn’t a great thing…

Riveting, I’m sure. But is it really that different from 5 years ago?

Back when I first started taking digital photographs in the mid-1990s (I know, we still listened to The Cardigans, Tracey Bonham, Marcy Playground and Tonic…) and I did some playing about with shooting in RAW format, comparing it to just using the JPEGs straight out of the camera. Back then, I decided that RAW was a complete waste of expensive memory stick space, because it was nigh-on impossible to spot the difference. I didn’t know why that was the case back then, but I think the answer is pretty clear right now: The dynamic range of 8-bit JPEG photographs was, in fact, pretty similar to that of the imaging sensor inside the camera.

A couple of years ago, I believe when I got the then-brand-new-on-the-market Canon EOS 20D, I decided to switch to RAW. I spotted that the quality was better than with JPEG, and I stuck with it. Mostly, I did it because I could never quite get the white balance right, and with RAW, you defer the decision until you’re at your computer, which always suited me quite well.

A couple of years ago, I believe when I got the then-brand-new-on-the-market Canon EOS 20D, I decided to switch to RAW. I spotted that the quality was better than with JPEG, and I stuck with it. Mostly, I did it because I could never quite get the white balance right, and with RAW, you defer the decision until you’re at your computer, which always suited me quite well.

More recently, I upgraded again, this time to a Canon EOS 450D, and the difference is quite noticeable – right from the start, I felt that the 450D was taking better photos than my old 30D, but I was struggling to figure out why. Ignoring the resolution (the 30D delivers 8.2mpx files, whereas the 450D has a slightly smaller imaging chip, but saves 12.2 mpx files to the memory card), the 30D is a better camera in all possible ways: Better top ISO, faster top shutter speed, better autofocus, quicker continuous drive, magnesium body, and so on and so forth. Nonetheless, I swear I was getting better photos with the 450D than with the 30D, on quite a consistent basis.

Then, finally, a few days ago, the penny dropped. I did some test shots on my 450D, setting it to shoot JPEGs, and then some more shooting RAW. The difference was vast – by using Photoshop’s built-in RAW editing tool, I was able to pull incredible amounts of extra information out of the RAW images from the 450D, compared to the ones from my 30D.

Now, add to that the fact that the Canon EOS 450D is Canon’s entry-level digital SLR, and that Canon’s R&D department haven’t been twiddling their thumbs in the meantime either – but as always, they save the best goodies for the people who cough up serious cash for the more hard-core semi-pro and professional lines of cameras.

I haven’t had a chance to have a go myself yet, but it’s rumoured from various fora that the Canon EOS 5D mk2′s RAW files (in addition to being full-frame and significantly higher resolution) have a 15-bit dynamic range which is completely out of this world.

What’s in it for me? How does this mumbo-jumbo make my photos better?

Much in the same way as how tastefully done multi-shot HDR photographs can look realistic and fantastic at the same time, single-shot HDR photographs can do a lot of good for you as a photographer.

Already, photographers all over are shooting in RAW instead of JPEG, because they’ve noticed that it’s a Better Thing – but only rarely do people stop to think why that might be. The reasons are above: you simply gain a lot more flexibility by having a higher dynamic range to play with, than if you limit yourself to the 8-bit limit of JPEG.

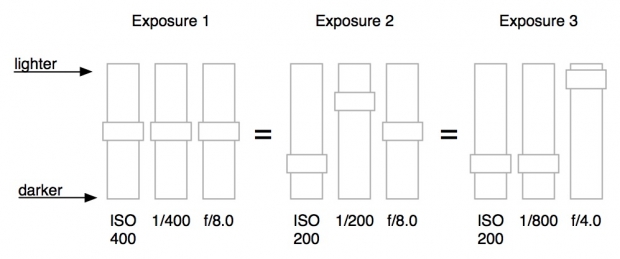

This extra flexibility isn’t just camera geekery either: It’s extra raw data in your photograph which you can genuinely use to deliver better final photographs. When I’m out taking photos in difficult lighting situations (such as dancing, concert photography or similar), I now routinely dial back the exposure by a full stop.

Yes, I know that it means that I lose some data in the top end, but because I’m shooting in RAW, I get away with it: The software will save me, and, more importantly, I can get a full stop faster shutter speed. When you’re out taking photos at a concert, the difference between 1/60th of a second and 1/100th are significant.

It isn’t just in poor light that the benefits are obvious, however – In fact, I can’t think of a single genre of photography where extra flexibility isn’t a good thing.

Look at it this way: If you go on holiday and bring two sweaters, you can always choose to wear the thick one or the thin one; when you’re shooting in RAW, you can always decide to go with the suggested automatic choices, and at worst you’ll have lost a few megabytes of storage space for a few hours (or days, or weeks, depending on how long you keep your photos on your camera), but seeing how cheap memory cards are these days, that’s hardly a huge problem – the extra flexibility is there when you need it, and it’s better to throw away data when you don’t need it, than to wish you had more when you don’t.

OK, I’m convinced, how can I join the fun?

So, how can you gain from all this extra goodness already? Easy – just set your camera to RAW. Stop reading right now, and set your camera to RAW. Yes, you. Yes, now. Then experiment. See how much your photos allow themselves to be tweaked without losing significant quality in the process.

What’s coming up in the future?

Frankly, I think digital SLR cameras can only go in one direction.

We already have higher resolutions than we know what to do with (I stick to my opinion that we never needed more than 6 megapixels, although it’s nice to be able to crop your images when needed without quality loss), and the top professional cameras are currently better, both in terms of dynamic range and resolution, than the top film-based SLR cameras ever were (and are rapidly closing in on medium format film cameras), and there are DSLR cameras that can film in full 1080p high definition video.

The way forward, is that dSLRs drop further in price, as the components that go into them get cheaper, and people get bored of the megapixel race. Canon, Nikon, if you’re listening, start selling a $200 8-megapixel sub-entry-level, and you’ll make enough money on the licensing of your lens mounts to make up for the loss in body sales; much like the way printer manufacturers (including Canon, interestingly), sell cheap printers with expensive ink refills.

The other boundary that needs to be pushed is dynamic range – I want a camera with completely ridiculous dynamic range, please, and I don’t mind if I have to sacrifice a bit of resolution or ISO speed to get there either. 20 bits worth would be nice. 24 bits if I can get it, so the dynamic range of my camera matches that of my screen.

Having such a camera means that I can become sloppy, but I can still rescue any photo unless I really balls it up. More importantly, however, it’ll allow me to do stunning HDR photos in a single click of the shutter. And, finally, it’ll be the last nail in the celluloid for those poor sods who still hang on to their film with a desperation which is inversely proportional to their dignity – and directly proportional to the grin on my face.

But seriously – start using RAW now, you might be amazed at how good your camera really is.

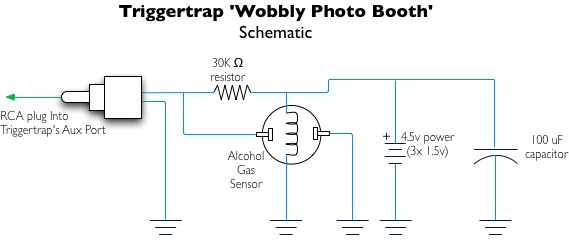

As a part of this project, I've been spending way more time than what's healthy looking at camera remote control cables, and I've done a few cool hacks to them. Among other things, I've looked at how you can

As a part of this project, I've been spending way more time than what's healthy looking at camera remote control cables, and I've done a few cool hacks to them. Among other things, I've looked at how you can

The human senses have an absolutely incredible dynamic range – think about it: when you’re inside a concert venue at a rock gig, you can hear every note and enjoy every instrument.

The human senses have an absolutely incredible dynamic range – think about it: when you’re inside a concert venue at a rock gig, you can hear every note and enjoy every instrument. A couple of years ago, I believe when I got the then-brand-new-on-the-market Canon EOS 20D, I decided to switch to RAW. I spotted that the quality was better than with JPEG, and I stuck with it. Mostly, I did it because I could never quite get the

A couple of years ago, I believe when I got the then-brand-new-on-the-market Canon EOS 20D, I decided to switch to RAW. I spotted that the quality was better than with JPEG, and I stuck with it. Mostly, I did it because I could never quite get the