When it comes to smartphone photography my default editing app is Snapseed. It does just about everything that I want in an app that I use on a device with a screen that's the size of the palm of my hand and it's intuitve. Sometimes, however, I find myself looking for a bit more control, the ability to adjust shadows, highlights, and midtones independently, or a white balance correction that is more fine-tuned. I've found it. It's called ColorTime.

ColorTime allows you to select between shadows, mid-tones, highlights, and saturation, adjusting the intensity on a colourwheel. Dragging up adds white or brightens the image; swiping your finger downwards introduces darker tones; and then you can increase warmer tones by swiping to the right and cooler colours by swiping leftwards.

Furthermore, you can paint particular areas of your image to adjust the tones selectively, or choose between the centre or edges of the image.

There are of course many occasions when any of this is useful, but I've found it particularly helpful for correcting the white balance in my iPhone photos, which always seem to be far too blue, and for adding a golden hour-like glow. If that's all far too subtle and practical for you, it's possible to make near-infinite adjustments: you keep moving your finger upwards (or downwards, left, right, four o'clock, 11 o'clock, whatever) until you reach the edge of the screen, and then you start over again.

The independent shadow, mid-tone, and highlight functions, in combination with the colour wheel, means that you can add blue to the highlights but orange to the shadows. If you want.

If you decide that you don't like you last adjustment, you hit the back arrow and it revokes it; if you decide that you've screwed it all up and want to start over, select the revert button. Should you not be able to decide, you can toggle between the original image and your adjusted image to decide which works best. Or you could select the animate function and let ColorTime present you with a loop of optins.

There is a crop and rotate function, but I haven't found it that easy to use. It feels underdeveloped and doesn't give you the control that you'd expect when the rest of the app is so responsive. It's not a huge problem, but for the moment, I will continue to crop in Snapseed.

I've really enjoyed using ColorTime and it has provided me with some terrific results. However, it is a learning curve. None of the buttons is labelled and I have occasionally found myself mistakenly adjusting entirely the wrong thing, but thankfully there is that undo feature. And there's a guide that is relatively easy to access.

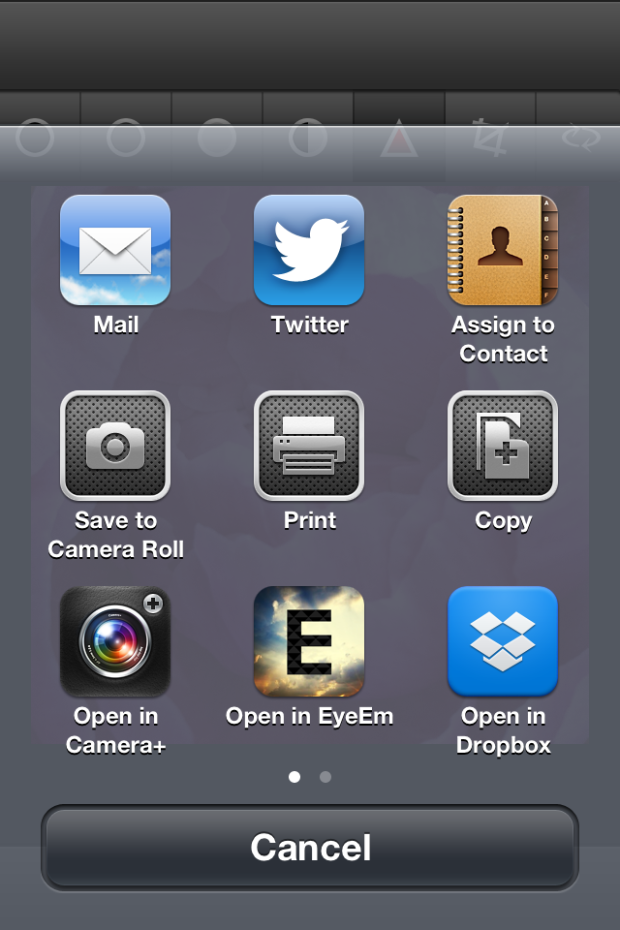

When you're done, you can save your fixed image to your camera roll, email it far and wide, tweet it, save it to your Dropbox, or choose from a few other options.

ColorTime is £1.49 in the App Store. For anyone who does even a moderate amount of iPhone photography, I reckon it's worth it.

A second way to test for lens flare is what is known as the ‘window test’. Aim the camera someplace indoors, but have a bright window just out of the view of the lens. If your image, upon developing ended up with the tell tale signs of lens flare, you know your camera can’t handle that sort of situation so well.

A second way to test for lens flare is what is known as the ‘window test’. Aim the camera someplace indoors, but have a bright window just out of the view of the lens. If your image, upon developing ended up with the tell tale signs of lens flare, you know your camera can’t handle that sort of situation so well. Okay, so I thought we were trying to avoid lens flare. Why would Photoshop come up with something people try to avoid? For the simple fact that lens flare shouldn’t always be avoided. In fact, it can a little something extra to your images when used in the right circumstances.

Okay, so I thought we were trying to avoid lens flare. Why would Photoshop come up with something people try to avoid? For the simple fact that lens flare shouldn’t always be avoided. In fact, it can a little something extra to your images when used in the right circumstances.