The more observant of Small Aperture’s loyal readers may have noticed that my blogging on Small Aperture has increased as of late. Well I have further bad news for you: I’ll be looking after our dear litle blogging site for the whole week. As a portrait photographer, I’m kicking off the week by looking at one of many portrait photographers whose work I enjoy, in the hope to inspire you, help you get more out of portraits and, ultimately, explain to you and to myself why I am particularly attracted to looking at and creating portraiture.

David Chancellor was the winner of 2010′s Taylor Wessing National Portrait Gallery Photo Prize – a wonderful exhibition which was displayed in, you guessed it, London’s National Portrait Gallery. I’m not going to look at his winning entry, “huntress with buck” – instead I’ll be looking at a portrait series of his, entitled “Boxers”.

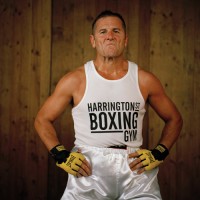

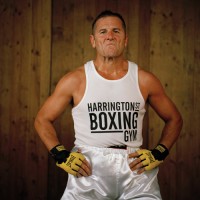

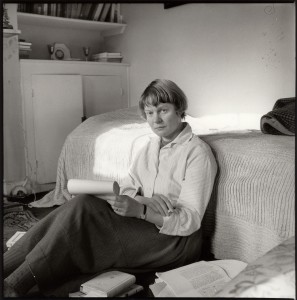

Daniel 'the mover' Avenir #I, from the series boxers, before and after

What I love about “Boxers” is the simplicity at the heart of the idea. It has that “why didn’t I think of that?” appeal to it. On the basic level, it’s a “before and after” spot the difference affair, showing each fighter just before their fight and immediately after their fight. This series has a quality that I see in many excellent pieces of portraiture (and any photography, for that matter): a simple, strong idea that has been executed exceptionally well.

From a technical perspective, they are absolutely beautiful – the lighting separates the boxers from the background so that they are especially prominent in the image. Another important detail is that the boxers are situated in the same position in the frame in their before and after shots (or, at least, those who were still able to sit up straight afterwards are!) which adds to the intensity of the “after” shot, as it almost seems like no time at all has passed between the two images, as they don’t appear to have moved anywhere in the interim.

So we’ve briefly examined the setup of the shots, but what takes a portrait from a pretty picture to something that holds your attention and gets you thinking beyond what you can initially see? To achieve this, we need a story.

The boxers in these images are not professionals. They are part of a phenomenon in South Africa known as “White Collar Boxing”, where men and women who have white collar jobs train for around three months to take part in a special boxing event against others of the same background. Not only that, but the boxers in this series are about to have their very first fight. Armed with this knowledge, whole new areas of intrigue are opened up to us, and this is where a well-lit, professionally composed image begins to turn into a real piece of portraiture.

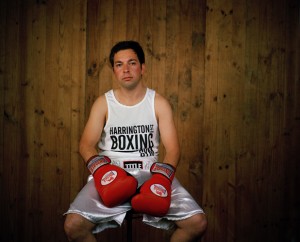

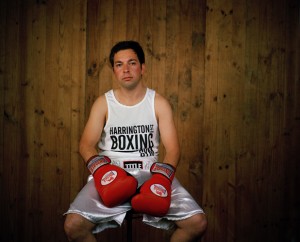

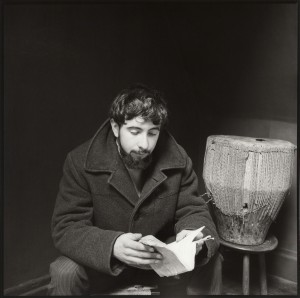

Daniel 'the mover' Avenir #II, from the series boxers, before and after.

Now, we are scrutinising their expressions prior to their fights. You can see the nervous energy they are harbouring under the surface, the kind that only builds up prior to a tense situation such as a physical fight, especially your first ever fight. Look at how some try harder to hide that nervousness, or indeed tackle it head on, especially for the camera. In a way, to point a camera at you the moment before your fight is the non-verbal equivalent of someone saying “how are you feeling about your first fight?” to which they answer non-verbally. I know that sounds a little pretentious, but go back and look at them with that idea in mind – they’re answering the question for you with their expression. Isn’t that just magical?

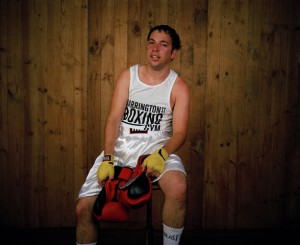

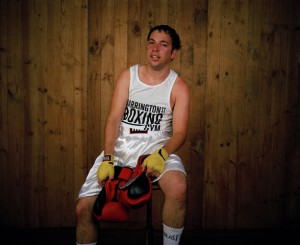

The “after” shots are similarly rich with story and intrigue. Did they win, or lose? What injuries do they have? Some of the boxers look so utterly exhausted, it gives across a feeling of relief and release, especially when compared to their “before” images, packed with nervous energy. My personal favourite is Steve “the paratrooper” Burke: the expression of absolute defiance and confidence combined with the pose is incredibly imposing and powerful.

I’m pretty sure he won.

The final sign of a great portrait or series of portraits is what it leaves you with, or what questions it makes you ask that go beyond the initial image. What fascinated me is considering what drives these “ordinary”, office job people to step into the ring and do something that, in my opinion, is incredibly daunting and frightening. Were some attracted to the thrill of the idea and the danger involved? Was it a result of feeling bored and stuck in a 9 to 5 driving the need to do something different? Was it the need to challenge themselves to instil a sense of progress and improvement in their lives? Bearing in mind that David tells us that White Collar Boxing is hugely popular across South Africa, it brings you to ask questions about the human condition, about what drives us.

Steve 'the paratrooper' Burke, from the series boxers, before and after.

David allows us to come to these conclusions and ask these questions ourselves, which is an important distinction to make. I’m all for setting up a series of portraits with a little bit of flavour text to tell you what you’re looking at, but it’s important to strike a balance. I have an intense dislike for photo projects where the photographer has written three pages of text to accompany the photographs, telling you what colour schemes to look out for, how the images all link to each other and which of your preconceptions will be challenged. This should all come across in the image: you shouldn’t be told how to feel (or what your prejudices and preconceptions are, for that matter).

And that, dear readers, is why I love “Boxers” and why I love portraiture. I’ll be taking a look at another portrait story later in the week.

We’ve included a couple of David’s “Boxers” images in this article purely for editorial and critique purposes. I hope my article has already moved you to do so, but please go and explore the full set on David’s site. Here’s a direct link – http://www.davidchancellor.com/docs/photos.php?id=3:5

Call me a romantic if you will, but there’s something that I find especially appealing about late night museum openings (maybe it’s reading too much Umberto Eco?), and I’m particularly looking forward to the Late Shift at the National Portrait Gallery on Friday 11 February. Nine portraits by Rankin of nine models who challenge the typical image of a fashion model in nine designs by fashion luminaries such as Dame Vivienne Westwood.

Call me a romantic if you will, but there’s something that I find especially appealing about late night museum openings (maybe it’s reading too much Umberto Eco?), and I’m particularly looking forward to the Late Shift at the National Portrait Gallery on Friday 11 February. Nine portraits by Rankin of nine models who challenge the typical image of a fashion model in nine designs by fashion luminaries such as Dame Vivienne Westwood.