It was a shame that the NPG couldn’t manage to open the first exhibition devoted to Ida Kar in over fifty years on Tuesday, what with it being International Women’s Day. It would have been fitting for such an influential figure in photography. She was, after all, the first photographer to be honoured with a major retrospective at a London gallery. (That was at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1960, by the way.) But that’s a minor thing, because the exhibition itself is the important bit.

Clare Freestone has brought together a collection of pictures that charts Kar’s career from his first studio in Cairo, through her days in London photographing the movers and shakers in the artistic scene, including her exhibitions at Gallery One and the Whitechapel Gallery, and on to her later reportage and travel photography. It shows how Kar adapted to her surroundings and changing circumstances. Although, she did favour working in just natural light, her camera of choice was a Rolleiflex, and she rarely changed lens.

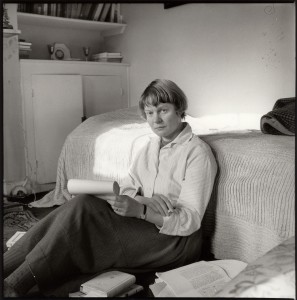

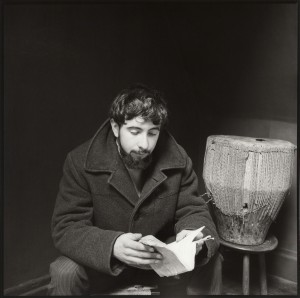

Kar was definitely an environmental portrait photographer. Yves Klein (‘the artist who painted nothing’) is pictured next to his blue sponge; Iris Murdoch is sitting with her back against her bed, surrounded by books and papers, Shostakovich is sitting at his piano. You can feel the souls of tortured artists and starving poets seeping through the bromide.

I have to admit that I’m not a great lover of environmental portraits, it’s a personal preference thing, but it doesn’t stop me from enjoying them and I did enjoy Kar’s. Still, it probably wasn’t surprising that I liked the picture of Barbara Hepworth best. She seems to be actually doing something towards creating a sculpture, rather than just being ensconced amidst her medium.

It’s these portraits, a who’s who of the London literati, that represent the pinnacle of Kar’s work. And they’ve impressed themselves on my memory better than the documentation of Kar’s trip to Cuba or her commission for The Tatler to Armenia, which was from where her family came.

You can get in to the Hoppé and Kar exhibitions on a double ticket, and I’d thoroughly recommend it. They make the most amazing contrast: Hoppé’s very personal, slowly generated and closely cropped portraits against Kar’s quickly shot environmental pictures. Hoppé who embraced technology and Kar who was much more set in her ways. It’s two very different means of telling a story through a photo, but both work.

Go see and enjoy. After all, as Sandy Nairne, the Director of the National Portrait Gallery put it, Kar is ‘admired by neglected’. I hope that this will change that.

Ida Kar: Bohemian Photographer, 1908-1974 runs from 10 March to 19 June 2011 at the National Portrait Gallery, St Martin’s Place, London, WC2H 0HE.

(Featured image: Dame Barbara Hepworth at work on the armature of a sculpture in the Palais de Danse, 1961, by Ida Kar (c) National Portrait Gallery, London.)

Many people do not wish to be photographed, for many different reasons. Native peoples, such as some Native Americans in the US, might refuse being photographed because they believe a mirror does not reflect reality, but a persons’ soul. A picture, taken by a device that relies heavily on mirrors, may therefore capture and enslave the soul. Sometimes, this restriction only counts for infants and children, as their souls are fragile, and can more easily leave the body.

Many people do not wish to be photographed, for many different reasons. Native peoples, such as some Native Americans in the US, might refuse being photographed because they believe a mirror does not reflect reality, but a persons’ soul. A picture, taken by a device that relies heavily on mirrors, may therefore capture and enslave the soul. Sometimes, this restriction only counts for infants and children, as their souls are fragile, and can more easily leave the body. In some countries, such as China, taking someone’s picture without their consent is simply extremely rude. Others might feel they are not photogenic, and do not want their face to be splashed all over Flickr. And you need to be wary that some locations (places of worship, official buildings and structures, museums and military bases) may prohibit photography for security reasons.

In some countries, such as China, taking someone’s picture without their consent is simply extremely rude. Others might feel they are not photogenic, and do not want their face to be splashed all over Flickr. And you need to be wary that some locations (places of worship, official buildings and structures, museums and military bases) may prohibit photography for security reasons. But, in general, rule number one is, get permission. It is essential that your behaviour and attitude is not one of right, but one of friendly coexistence. When you smile and nod while pointing at your camera, it is pretty clear what you want. This might sometimes mean that your photo will not be as spontaneous as you might wish, but at least you will not end up in sticky situations where the subject feels their personal space, or religion is violated. Especially on the topic of photographing children, you need to be very cautious, make sure to ask the parents or guardians for permission, no matter where in the world you are.

But, in general, rule number one is, get permission. It is essential that your behaviour and attitude is not one of right, but one of friendly coexistence. When you smile and nod while pointing at your camera, it is pretty clear what you want. This might sometimes mean that your photo will not be as spontaneous as you might wish, but at least you will not end up in sticky situations where the subject feels their personal space, or religion is violated. Especially on the topic of photographing children, you need to be very cautious, make sure to ask the parents or guardians for permission, no matter where in the world you are. Rule number three is that if someone asks you to stop taking photos, either verbally, by turning away, by looking uncomfortable, or by running for cover, as happened to me in Vietnam, stop. No matter the reason why someone might want you to stop, it is important that you keep in mind what Darren Rowse

Rule number three is that if someone asks you to stop taking photos, either verbally, by turning away, by looking uncomfortable, or by running for cover, as happened to me in Vietnam, stop. No matter the reason why someone might want you to stop, it is important that you keep in mind what Darren Rowse