Whenever a new excuse for buying stuff (Christmas? Birthdays?) rolls around, the retailers are rubbing their money-grabbing little paws in glee, in anticipation of making a killing over the holiday seasons. Be that as it may, fact remains that there is a lot of choice out there, and whether you are buying your first camera, or whether you are out shopping for a friend of family member, you might need a hand.

Welcome to the 7th edition (!) of my in-depth guide to choosing an entry-level dSLR camera: What should you be looking for, what should you be buying, and why? It’s all in our handy shopping guide, right here…

Where should you even begin?

Once you’ve decided to start looking for a dSLR, you might have some reason in mind already. Perhaps you feel as if you’re outgrowing your compact camera, whether that’s creatively or technically. Maybe you’re not really feeling as if you’re challenging yourself enough as a photographer. Either way, you’ve decided to go play with the big boys – welcome aboard!

The first and most important thing you need to know is that there aren’t any really bad digital SLR cameras out there.

In fact I would argue that there aren’t actually any bad digital cameras on the market anymore in general – stick to a respected camera brand, and you’re home free. If we’re looking at compact cameras, you can buy a respectible camera for under $100 – the Canon Powershot A2200, for example wil set you back $99 or thereabouts, and is a lot of camera for your hard-earned dollars.

Anyway, we were talking about dSLR cameras. Here are a few things you should be looking at..

Things to consider before making your choice

Do you already own a SLR camera?

If you have already bought into a particular brand of camera, take a good, hard look at your lenses. If you’ve bought a lot of high-end lenses and flashguns etc, swapping from one brand to another might have a lot of hidden costs in them. On the other hand, if you have a lot of old, tattered equipment with scratched lenses, see it as an opportunity: eBay off the lot, and start afresh.

Canon or Nikon?

This is a perennial question which I’m not going to go anywhere near.I defy anybody to be able to tell the difference between a camera taken with a Canon or with a Nikon camera. Or a Sony. Or a Panasonic. Or a Sigma. Things have moved on hugely since the raging Canon-Nikon debates of the early 1980s (and they scarcely made all that much sense then).

Whichever camera system you buy into, you’re going to live with for a while (probably), so do think about it. You – not your camera equipment – is going to be the bottleneck, so don’t worry too much about what you might have heard form the old graybeards…

Buying into a system?

You know best what kind of a photographer you are. If you’re likely to start buying high-end lenses (or ‘fast glass’, as it’s frequently called among seasoned photographers), then you have two choices: Canon or Nikon. There are a lot of other people out there building great DSLR cameras, but once you start talking seriously high-end equipment, it’s one of the two big ones, I’m afraid.

On the other hand, if you are a semi-serious hobbyist, don’t discard other camera brands out of hand: Sony, Olympus and Panasonic are building some very capable cameras indeed – with some serious money-saving opportunities, too!

Body or glass?

If you have to choose between buying an expensive body and cheap glass or a cheap body and expensive glass, then go for the posh lenses. Every time. Personally, I am still using lenses that I bought nearly 10 years ago, even though I’ve changed my camera bodies half a dozen times since: You can take fantastic photos with an entry-level body and expensive lenses.

Putting bargain lenses on a top-level body is, frankly, a complete waste of money. Even better: Buy yourself a nice prime lens, and be amazed at what your camera body can do.

Megapixels?

In general, don’t worry about megapixels – most dSLR cameras come with 10 megapixels or more, and that’s enough. Hell, there’s even a prominent group arguing that more pixels aren’t necessarily better, and that 6mpx is all you need, really. I’m inclined to agree – you very rarely use them at full resolution anyway. What I’m trying to say is that Megapixels should be the last thing you look for in a digital camera in general – and a dSLR especially.

The above photo was taken with... an iPhone. Proving that any camera can take a good photo.

So, to summarise:

- Don’t worry too much about the brand of your camera body

- Buy Canon or Nikon if you anticipate dropping a lot of money on lenses in the long run

- Spend your money on lenses, not camera bodies

- Oh. and also consider looking into EVIL cameras - they're smaller and lighter than SLR cameras, but you keep the ability to swap lenses, and they can take great-quality photos! (loads more info about EVIL photography here)

3 great bargains

So, you’ve decided to leap into the pool of DSLRs, but you want to spend as little money as possible? These three cameras are your best options:

Sony Alpha A390

The Sony Alpha 390 is an absolute bargain, and a great entry into the world of SLR. You get 14.2 mpx (more than enough), RAW image format (which is a must), and an incredibly nifty little feature: In-camera optical ‘SteadyShot’ image stabilisation! This means that any lens you connect to the Sony Alpha camera will be image stabilised – this is a feature you pay tons of money for in the lenses of other camera manufacturers!

The Sony Alpha 390 is an absolute bargain, and a great entry into the world of SLR. You get 14.2 mpx (more than enough), RAW image format (which is a must), and an incredibly nifty little feature: In-camera optical ‘SteadyShot’ image stabilisation! This means that any lens you connect to the Sony Alpha camera will be image stabilised – this is a feature you pay tons of money for in the lenses of other camera manufacturers!

The Sony Alpha lenses are compatible with Minolta AF and Konica lenses, so you get a reasonably good choice of glass, and the camera has a pretty wide shutter speed range of 30 seconds to 1/4000th of a second.

On top of all this, the Sony can be picked up with a fabulous kit lens – sure, it’s not the best glass you can buy, but who cares when you’re eager to get started. You can always chuck away (or eBay) the kit lens later, and upgrade to something better, once you know what kind of photos you’re likely to be taking!

You can get the Sony Alpha 390 with a kit lens from Amazon.com for about $449 and from Amazon.co.uk for about £349.

Canon EOS 1100D / Canon Rebel T3

The world of digital cameras has come a very long way indeed. I remember buying my first DSLR in the mid-to-late 1990s, and, well, you’d pay a small fortune for something that wasn’t all that amazing.

The world of digital cameras has come a very long way indeed. I remember buying my first DSLR in the mid-to-late 1990s, and, well, you’d pay a small fortune for something that wasn’t all that amazing.

These days, though, you’re not needing to spend that much money to pick up a big-brand SLR camera. Obviously, Canon felt Sony and the other budget-DSLR manufacturers breathe down their neck, and they had to respond. And boy, did they respond: The EOS 1100D / Rebel T3 is one heck of a camera. Sure, so they’ve cut a few corners here and there, but, frankly, I don’t give a damn.

Personally, if I were to buy a SLR today, I’d buy one of two cameras: A Canon EOS 5D mk III (which costs a small fortune), or a 1100D / T3. Why? Because the imaging sensor is brilliant, and you can start saving up to buy lenses that will be with you and your camera system for a decade or more. When you finally out-grow the 1100D, eBay it and buy a mid-range camera (like the Canon 600D), or start looking at spending serious money for a serious camera (Canon 5D mk III if you want full-frame coverage, 7D if you don’t) – but none of the money you spent on lenses was a waste: It’ll all still be there, ready for you to snap away.

Of the bargain-snappers, only the 1100D / T3 has a CMOS sensor – which makes a surprising difference in image quality: Not necessarily better, but for some reason the grain on a CMOS sensor at higher ISO is a lot more similar to film than CCD sensors pushed to the limit… All of which means that the 1100D photos ‘feel’ more natural when you look at them.

You can get the Rebel T3 from Amazon.com for about $490 or the Canon 1100D from Amazon.co.uk for about £400 – both with a Canon EF-S 18-55 kit lens.

Nikon D3100

Nikon’s baby camera is the D3100 – and it’s another bloody strong contender to the bargain crown. It comes with a super-advanced light meter – the 3D Matrix metering system borrowed from far more expensive Nikon cameras, which means that the Nikon is definitely the most capable in terms of getting the light measurements right.

Nikon’s baby camera is the D3100 – and it’s another bloody strong contender to the bargain crown. It comes with a super-advanced light meter – the 3D Matrix metering system borrowed from far more expensive Nikon cameras, which means that the Nikon is definitely the most capable in terms of getting the light measurements right.

The other thing the D3100 gets right is that it has a fabulous 3-inch LCD screen on the back of the camera, which makes a huge difference when you’re checking your photos in the field, to ensure you've captured what you're looking for all right.

Just like the Canon camera, the Nikon is an opportunity to start climbing the ladder – Buy the most expensive lenses you can afford, get some tasty flashguns, and they’ll be with you for a long time indeed.

I have to admit that I’m a Canon man at heart (I’ve used Canon cameras since I stole my dad’s Canon A1 out of the cupboard when I could barely walk. I didn’t break it, luckily), but it’s starting to seem as if Nikon currently have a nicer progression through the cameras – the D3100 is a peach, and the D5000 or D5100 – which is the next step up without being that much more expensive – is a deceptively simple, yet very serious, camera, for serious photographers.

You can pick up a D3100 from Amazon.com for about $640 and from Amazon.co.uk for £440 or so.

So… What should I choose?

If you want to take the step from compact cameras to SLRs, but foresee that you’ll continue being a casual amateur, go for the Sony. It’s a great little camera, a fantastic bargain, and the lenses available are not bad at all.

If you are ambitious in your photography, grab a dice. Throw it. Even numbers are Canon. Odd numbers are Nikon. They’re both absolutely brilliant cameras, and – considering what you get for your money – bargains. The Canon has a slightly better imaging sensor (but you wouldn’t be able to tell until you’re at higher ISO speeds) and the Nikon has a marginally better light meter (which doesn’t make that much difference in real life) and a better screen (which does). Seriously, if you’re having trouble making up your mind, throw the dice. It’ll save you a lot of headache.

Any final tips?

I know I’ve repeated this several times in this article, but if you’re new to SLRs, I would advise to buy the entry-level model from a manufacturer. Start taking photos – you won’t out-grow your camera body for a while, trust me on that, but you might out-grow your lenses. Start by buying a ‘Nifty Fifty‘ (a 50mm prime lens). Most manufacturers have a f/1.8 which is good and a f/1.4 which is great…

Once you have one of those, start thinking about the type of photography you do. If you want to start shooting macro, you’ll need to start looking into a macro lens. If you want to photograph gigs or wildlife, you’ll want a fast tele-zoom (I can’t recommend Sigma’s 70-200mm f/2.8 DSM lens highly enough – it’s a bargain for what you’re getting). If you’re more into in-door or landscape photography, you want to go wider – but only you know exactly what you want.

Buying cheap lenses is false economy – unless you don’t really know what you want to take photos of. If you’re just experimenting, flailing around a little (as we all are, at first), stick with your prime and your kit lens for a while. If you find yourself at the wide end of your kit lens most of the time, perhaps it’s a sign you need to spend a bit of cash on a wider lens. If you’re constantly at full zoom… well, you figure it out.

If you’re worried about spending hundreds – if not thousands – of dollars (or pounds, should you be on my side of the pond) on glass, go ahead and rent the lens you’re considering for a few weeks. Does it do everything you want it to? Is it too heavy? Does it feel right? Is it fast enough? If you’re not happy, rent a different lens, and keep searching. When you find the right lens(es) for you, you’ll know it – and that’s the right time to start shelling out the big bucks.

Seriously: Buy glass first. (If you want to learn more about lenses, I've got everything you could possibly want to know right here...) Worry about camera bodies later. By the time you have bought some serious lenses, you’ll know what you need from a camera (wide angle? Full-frame sensor. Sports? Fast, high-frames-per-second camera. Walking a lot? Buy a capable, but light-weight camera body… Etc)… But it’s a supremely silly thing to do to spend a lot of money on a camera body until you know what you really want/need.

So, Haje, what do you use?

I’ve had a lot of cool cameras in my time – I worked as a freelance photographer for a while, and bought all the top-shelf gear. At one point, I drove around in a £1,300 car with £49,000 worth of camera equipment in the boot. I think it’s pretty safe to say that I’m a gadget nut, and a camera aficionado to boot.

I’ve had a lot of cool cameras in my time – I worked as a freelance photographer for a while, and bought all the top-shelf gear. At one point, I drove around in a £1,300 car with £49,000 worth of camera equipment in the boot. I think it’s pretty safe to say that I’m a gadget nut, and a camera aficionado to boot.

… Which is why it might surprise you that currently, my main camera is... a Canon EOS 550D. It’s not the newest camera on the market anymore. It never was the best. But it does everything I need from a camera: It’s plastic, so it’s reasonably light weight. It’s relatively sturdy. It uses SD cards (which plug straight into my MacBook Pro – it’s a small thing, but I like it).

The five-fifty takes all my lenses (I have loads, but the ones I’ve used in the past 6 months are a Sigma 17-35mm f/2.8-4.0, a Canon 50mm f/1.4, a Sigma 70-200 f/2.8, and my Lensbaby G3 lens), and it doesn’t look too conspicuous. It’s also cheap enough that I’m not too crazy worried about it getting stolen or dropping it. All in all: Perfect for my uses. And it's one cheapest camera you can buy with a Canon badge on it.

This article was first published in 2007, but has been updated with the most relevant information every year since. It was most recently updated in April 2012.

The Sony Alpha 390 is an absolute bargain, and a great entry into the world of SLR. You get 14.2 mpx (more than enough), RAW image format (which is a must), and an incredibly nifty little feature: In-camera optical ‘SteadyShot’ image stabilisation! This means that any lens you connect to the Sony Alpha camera will be image stabilised – this is a feature you pay tons of money for in the lenses of other camera manufacturers!

The Sony Alpha 390 is an absolute bargain, and a great entry into the world of SLR. You get 14.2 mpx (more than enough), RAW image format (which is a must), and an incredibly nifty little feature: In-camera optical ‘SteadyShot’ image stabilisation! This means that any lens you connect to the Sony Alpha camera will be image stabilised – this is a feature you pay tons of money for in the lenses of other camera manufacturers! The world of digital cameras has come a very long way indeed. I remember buying my first DSLR in the mid-to-late 1990s, and, well, you’d pay a small fortune for something that wasn’t all that amazing.

The world of digital cameras has come a very long way indeed. I remember buying my first DSLR in the mid-to-late 1990s, and, well, you’d pay a small fortune for something that wasn’t all that amazing. Nikon’s baby camera is the D3100 – and it’s another bloody strong contender to the bargain crown. It comes with a super-advanced light meter – the 3D Matrix metering system borrowed from far more expensive Nikon cameras, which means that the Nikon is definitely the most capable in terms of getting the light measurements right.

Nikon’s baby camera is the D3100 – and it’s another bloody strong contender to the bargain crown. It comes with a super-advanced light meter – the 3D Matrix metering system borrowed from far more expensive Nikon cameras, which means that the Nikon is definitely the most capable in terms of getting the light measurements right.

I’ve had a lot of cool cameras in my time – I worked as a freelance photographer for a while, and bought all the top-shelf gear. At one point, I drove around in a £1,300 car with £49,000 worth of camera equipment in the boot. I think it’s pretty safe to say that I’m a gadget nut, and a camera aficionado to boot.

I’ve had a lot of cool cameras in my time – I worked as a freelance photographer for a while, and bought all the top-shelf gear. At one point, I drove around in a £1,300 car with £49,000 worth of camera equipment in the boot. I think it’s pretty safe to say that I’m a gadget nut, and a camera aficionado to boot.

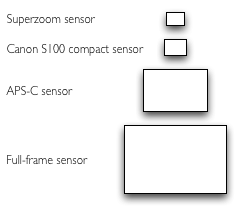

Well, there are a couple of things the compact camera manufacturers do. For one thing, they tend to use rather small sensors; both of the cameras mentioned above use 6.17 x 4.55 mm sensors. That is... Tiny. Compare those numbers to the sensor used in Canon's top-of-the-range compact shooter, the

Well, there are a couple of things the compact camera manufacturers do. For one thing, they tend to use rather small sensors; both of the cameras mentioned above use 6.17 x 4.55 mm sensors. That is... Tiny. Compare those numbers to the sensor used in Canon's top-of-the-range compact shooter, the